Next time US-Americans are calling socialism = „the devil“ – take a look at Marinaleda – and tell me: How exactly do you define socialism? Maybe we need a new word = „the devil“.

how a spanish major tunred 50% unemployment into 0% by occupying land…

Arte Reverse Landgrabbing: THE LAND BELONGS TO EVERYBODY! NOT THE 1% SUPER RICH!

Links:

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/04/spain-utopia-160418120509828.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/20/marinaleda-spanish-communist-village-utopia

Die Spekulationen auf Grund und Boden treiben nicht nur die Mieten sondern auch die Lebensmittelpreise in die Höhe.

Landgrabbing von unten: Andalusischer Bürgermeister aus Marina Leda luxt adeligen 1100ha brach liegendes (!) Land ab und schafft Arbeitsplätze.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marinaleda

Gegenentwurf: Jeder gibt 100€, davon kauft eine gemeinnützige Genossenschaft Acker-Grund, bewirtschaftet diesen, und die Anteilnehmer bekommen eine „Dividende“ in Bio-Kartoffeln?

Genial oder? 😉

Ein sehr interessantes projekt ist die Seite landshare.net

More about Marina Leda and their people:

Aljazeera.com

Inside Spain’s Utopia

Is a communist village in Andalusia where most villagers work for a cooperative really as utopian as it seems?

By

Hagar Jobse

Marinaleda, Spain – At first sight, Marinaleda appears to be a typical Andalusian village with white-washed houses and streets that do not come alive until after the sun goes down.

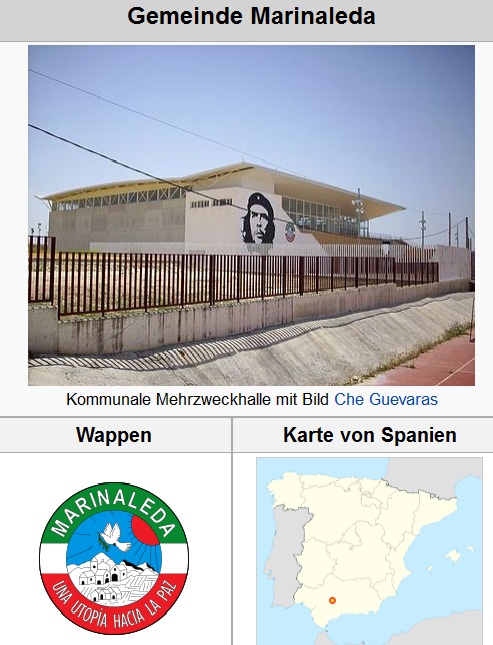

But if you look closely enough, there are signs that things are different in this small town of 2,700 inhabitants: there is the portrait of Che Guevara that adorns its sports centre and the notable absence of commercial billboards.

Marinaleda has been governed by Juan Manuel Sanchez Gordillo, its self-declared communist mayor, for more than 35 years. And while the unemployment rate in the rest of Andalusia is 29 percent, it barely touches five percent here.

The majority of Marinaleda’s inhabitants work for the village’s agricultural cooperative and earn the same salary – 47 euros (about $54) for a six-and-a-half hour working day. This equates to a monthly salary of 1,200 euros (about $1,370), which might seem low, but it is significantly more than the Spanish minimum wage of 764 euros a month (about $870).

Life in the village is also much cheaper than in the rest of the region. For 15 euros a month, inhabitants can pay off their mortgage. The same price gets them membership of the sports centre, or a kindergarten place for their child. The local government provides three free school meals a day. As a result, even the small number of unemployed inhabitants are able to make ends meet with the 400 euro jobseeker’s allowance provided by the Andalusian government.

|

| New government-owned houses are being built in the village [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

The secret of Marinaleda

Marinaleda’s „secret“ lies in the 1,200 hectares of land just outside the village.

A message written on the wall of an old farmhouse sheds light on the village’s history and ethos. „This land belongs to all the unemployed labourers of Marinaleda,“ it declares.

Twenty-five years ago, the El Humoso farmhouse and its estate belonged to a wealthy landowner, who left the land uncultivated for most of the year while more than 60 percent of Marinaleda’s inhabitants were unemployed and living in extreme poverty.

Then, in 1979, after being elected mayor, Juan Manuel Sanchez Gordillo started campaigning for land reforms to benefit Marinaleda’s unemployed and landless labourers. Twelve years of strikes, during which villagers would occupy the land surrounding Marinaleda, followed.

In 1991, the regional government finally awarded the farm and its 1,200 hectares of land to the village. The village’s agricultural cooperative was established soon after.

The cooperative aimed to grow those crops that required the greatest amount of labour, such as red peppers, paprika and artichokes, so as to create as many jobs as possible.

A few years later, Marinaleda built its first processing factory, to can and jar the cooperative’s produce.

For the past 24 years, the farm and the factory have provided employment to Marinaleda’s inhabitants, while all of the cooperative’s profits are invested in the creation of new jobs. The village’s mayor and members of the local council work voluntarily at the cooperative but have other jobs through which they earn a wage. For many years, the mayor worked as a history teacher at the local high school.

|

| Marinaleda’s ’secret‘ lies in the 1,200 hectares of land just outside the village [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

‚What else could I wish for?‘

The factory, adorned with huge paintings of a pepper, a chili and an artichoke, is located on the edge of the village.

Inside, around 30 women wearing mint green vests are lined up along a conveyor belt, de-stemming peppers one by one.

Among them is 48-year-old Asencion Torres, who works here each day from 6.00 in the morning until 2.30 in the afternoon. Nowadays, she earns enough money to make ends meet, but as a young girl her family could barely afford to buy food.

„Although my father sometimes did small jobs for the landlord, he barely earned any money,“ she says. „We never had enough to eat. Having a job was a real privilege.“

Asencion’s colleague, Isabel Montesinos, 47, has worked at the factory since she was 29, and for that she is grateful. „I am so happy with this job. Before I started at the factory I harvested the crops. That was much tougher,“ she says.

Montesinos was also one of the first of Marinaleda’s inhabitants to receive a house from the government. Now, there are 250 government-owned houses in the village.

The government provides or pays for the building materials so that the members of the cooperative can build their own house. But while they build them themselves – often with the help of other cooperative members – and pay a mortgage to cover the building costs, the houses are essentially government-owned, and inhabitants aren’t allowed to pay off any more than 15 euros a month. The aim is to prevent property speculation.

And Montesinos says she couldn’t be happier with the situation. „I have my own house and two cars. What else could I wish for?“ she asks. „I owe that to the mayor.“

|

| The factory cans and jars the produce produced on the land. Many villagers start work here upon finishing school at 16 [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

‚We have a better quality of life‘

Montesinos isn’t the only one who is grateful. Sanchez Gordillo has governed Marinaleda for more than 35 years and continues to be re-elected with an absolute majority.

Even many younger residents who have not lived through the hardships of the pre-Sanchez Gordillo era seem to be content with the mayor’s policies.

Virginia Sanchez, 32, sits at the bar of one of three cafes in the town. She was born and raised in Marinaleda and says she wouldn’t change it for the world.

|

| Virginia Sanchez quit school when she was 16. She works on the farm from 7.30 in the morning until 3.30 in the afternoon [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

„In Marinaleda, we have a better quality of life than people in the rest of Andalusia,“ she explains.

Every day, Sanchez works on the Humoso farm from 7.30 in the morning to 3.30 in the afternoon. When asked whether she likes her job, she shrugs her shoulders and answers that it’s fine. „I quit school when I was 16, and I was glad that I could finally start working,“ she says.

Maria Jose Bermudez, 21, and Yamira Prieta, 21, are sitting on garden chairs outside the factory, enjoying their 30-minute break. They have worked here since they were 16.

„If you want to complete high school you have to transfer to a school in Estepa, the nearest village,“ Prieta explains.

They say they don’t know anyone who finished high school.

‚If you do not work, you do not earn anything‘

Indira Garcia, 22, is one of the few in the village who did finish high school. She is now studying food sciences at the University of Granada.

She has returned to Marinaleda for a month to manage the factory’s product control and registration process. Dressed in a lab coat, she makes notes in a log book. She doesn’t mind missing lectures for a month, she says. „I like working in the factory,“ Garcia explains.

|

| Indira Garcia, 22, is one of the few in the village who did finish high school [Hagar Jabse/Al Jazeera] |

When asked whether she would like to work in Marinaleda after finishing her degree, she answers hestitantly. „Of course,“ she says. But Garcia is ambitious and would like a full-time job in product control. She is unsure if such an opportunity exists in Marinaleda.

And while most of Marinaleda’s inhabitants have a job, they do not necessarily have a 40-hour work week, and Garcia admits that there is often no work between harvests, a period that lasts for around a month. „If you do not work, you do not earn anything and are dependent upon the 400 euro allowance,“ she explains.

Without full-time employment, many 20-somethings spend much of their time sitting around outside one of the village’s three cafes. When asked if they shouldn’t be at work, one of them shrugs his shoulders and responds: „Not today.“

They seem to prefer not to talk about it. And they’re not the only ones. When asked her opinion on the mayor’s policies, a waitress in one of the town’s bars replies abruptly: „I prefer to keep out of that.“ Two young pharmacy assistants do not want to talk either.

Miguel Gomez, 29, is sitting with friends at the terrace of a bar. He works at his father-in-law’s cattle ranch, but used to be a freelance electrician operating in nearby villages. Then the economic crisis started and he began losing clients. He was eventually forced to find other employment.

Gomez falls silent when asked why he doesn’t work for the cooperative. He eventually admits that he used to. Between the age of 13 and 18, he worked on the farm for free. „Voluntary work is sometimes the only way to secure employment at the cooperative later on in life,“ he says, tapping his fingers nervously on the plastic table.

|

| Government-owned houses in Marinaleda [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

Meeting the mayor

Mayor Sanchez Gordillo lives in one of Marinaleda’s government-owned houses. It is typical of the others, but his is located directly in front of the large, austere-looking town hall.

At 67, the mayor looks a little frail. It is hard to imagine that this is the man who has called the Spanish king a thief in interviews and, in 2012, led members of the Andalusian Workers‘ Union in a raid on a supermarket in a nearby village so as to „re-distribute“ wealth from the rich to the poor.

While he still fulfils his duties as mayor, he explains that, because of his poor health, he retired from his job as a history teacher two years ago,

From speaking to Marinaleda’s inhabitants, it seems that the mayor was one of the few to enjoy employment beyond the cooperative.

But he paints a different picture. „There are plenty of job opportunities beyond the cooperative, such as teaching at the local high school, but also working at the kindergarten or doing social work,“ he says, although he does acknowledge that finding work at the cooperative is easier than finding highly-skilled work in the village.

People can also start their own businesses, he says. At the moment, there are about 20 small companies in Marinaleda, including three cafes, two pharmacies and a bridal shop. Although large franchises are not allowed to establish branches in the village, the mayor says he doesn’t want to stand in the way of entrepreneurship – „as long as their businesses do not become too large“.

He doesn’t explain what „too large“ might look like and says he cannot recall how many business licences he has granted in the past couple of years, although he says everyone who applied for one got it.

|

| The message on the wall in Marinaleda reads: ‚Sovereignty and socialism‘ [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

‚Blacklisted‘

In a large restaurant just outside the town, 27-year-old Antonio Saavedra is taking orders. He works here for six half days a week and earns 1,100 euros (around $1,258) a month. When he isn’t at the restaurant, he is helping his father at the family’s poultry farm. He says he is happy he doesn’t work at the cooperative.

„Have you seen these guys hanging around the village?“ he asks without waiting for an answer. „That is because a 40-hour work week does not exist in Marinaleda. Because the work in the cooperative is divided between all inhabitants, many people do not get more than six days a month.“

Saavedra and his father say they have not been granted the business licence they applied for three years ago. Their poultry farm was built long before Sanchez Gordillo became mayor, but three years ago they decided to open a second business for which they needed his approval. They say they are still waiting.

„The mayor simply does not want inhabitants to undertake any entrepreneurial activity,“ says Saavedra.

„If you try to make an appointment, you are being told the mayor is not around. That is the excuse we have been hearing for over three years now.“

Saavedra says that, if he could, he would leave Marinaleda and start his business elsewhere.

„But I cannot do that,“ he explains. „My father is ill and I am the only one in the family who still lives here. I have to stay here to take care of him.“

When I return to the restaurant to speak to Saavedra again, the boss says he doesn’t have an employee by that name.

But five minutes later Saavedra walks in. Explaining why he’d given a false name, he says: „If the mayor hears what I told you, he will never give me the licence we have been waiting for for so long.“

He isn’t keen to talk any more, so makes his excuses and returns to work.

|

| A cooperative worker harvests olives [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

‚Revolutionaries and troublemakers‘

The owner of a small shop just outside the town explains: „Anyone who says something negative about the mayor or his policies ends up on a blacklist and will not receive any more work from the cooperative. This happened to someone I know.

„The girl openly criticised the mayor. She has now been out of employment for a whole year,“ says the shop owner, who asked to remain anonymous.

She says that the few people who continue their education after high school usually move away from Marinaleda. But even they struggle to find a job upon graduating, she adds. „Companies in villages and towns neighbouring Marinaleda are reluctant to hire people from here. You see, inhabitants of this village are stereotyped as revolutionaries and troublemakers. So if you are from Marinaleda, you start your job search with a disadvantage.“

Many of Marinaleda’s buildings – including the town hall, the sports centre and the school – display the town’s slogan: „Marinaleda, a utopia for peace.“

Opinions seem to be mixed on just how true that is.

„Some of my friends from nearby villages envy me for living here,“ says villager Virgina Sanchez.

The shop owner who asked not to be named agrees. „People in Marinaleda generally have a better quality of life than many others in the rest of the country,“ she says. „That is, as long as you do not criticise the government and aren’t ambitious.“

|

| Marinaleda’s sports centre with its picture of Che Guevara [Hagar Jobse/Al Jazeera] |

Source: Al Jazeera

src:

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/04/spain-utopia-160418120509828.html

theguardian.com

In 2004, I was leafing through a travel guide to Andalusia while on holiday in Seville, and read a fleeting reference to a small, remote village called Marinaleda – „a communist utopia“ of revolutionary farm labourers, it said. I was immediately fascinated, but I could find almost no details to feed my fascination. There was so little information about the village available beyond that short summary, either in the guidebook, on the internet, or on the lips of strangers I met in Seville. „Ah yes, the strange little communist village, the utopia,“ a few of them said. But none of them had visited, or knew anyone who had – and no one could tell me whether it really was a utopia. The best anyone could do was to add the information that it had a charismatic, eccentric mayor, with a prophet’s beard and an almost demagogic presence, called Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo.

Eventually I found out more. The first part of Marinaleda’s miracle is that when its struggle to create utopia began, in the late 1970s, it was from a position of abject poverty. The village was suffering more than 60% unemployment; it was a farming community with no land, its people frequently forced to go without food for days at a time, in a period of Spanish history mired in uncertainty after the death of the fascist dictator General Franco. The second part of Marinaleda’s miracle is that over three extraordinary decades, it won. Some distance along that remarkable journey of struggle and sacrifice, in 1985, Sánchez Gordillo told the newspaper El País: „We have learned that it is not enough to define utopia, nor is it enough to fight against the reactionary forces. One must build it here and now, brick by brick, patiently but steadily, until we can make the old dreams a reality: that there will be bread for all, freedom among citizens, and culture; and to be able to read with respect the word ‚peace ‚. We sincerely believe that there is no future that is not built in the present.“

As befits a rebel, Sánchez Gordillo is fond of quoting Che Guevara; specifically Che’s maxim that „only those who dream will someday see their dreams converted to reality“. In one small village in southern Spain, this isn’t just a T-shirt slogan.

In spring 2013 unemployment in Andalusia is a staggering 36%; for those aged 16 to 24, the figure is above 55% – figures worse even than the egregious national average. The construction industry boom of the 2000s saw the coast cluttered with cranes and encouraged a generation to skip the end of school and take the €40,000-a-year jobs on offer on the building sites. That work is gone, and nothing is going to replace it. With the European Central Bank looming ominously over his shoulder, prime minister Mariano Rajoy has introduced labour reforms to make it much easier for businesses to sack their employees, quickly and with less compensation, and these new laws are now cutting swaths through the Spanish workforce, in private and public sectors alike.

Spain experienced a massive housing boom from 1996 to 2008. The price of property per square metre tripled in those 12 years: its scale is now tragically reflected in its crisis. Nationally, up to 400,000 families have been evicted since 2008. Again, it is especially acute in the south: 40 families a day in Andalusia have been turfed out of their homes by the banks. To make matters worse, under Spanish housing law, when you’re evicted by your mortgage lender, that isn’t the end of it: you have to keep paying the mortgage. In final acts of helplessness, suicides by homeowners on the brink of foreclosure have become horrifyingly common – on more than one occasion, while the bailiffs have been coming up the stairs, evictees have hurled themselves out of upstairs windows.

When people refer to la crisis in Spain they mean the eurozone crisis, an economic crisis; but the term means more than that. It is a systemic crisis, a political ecology crack’d from side to side: a crisis of seemingly endemic corruption across the country’s elites, including politicians, bankers, royals and bureaucrats, and a crisis of faith in the democratic settlement established after the death of Franco in 1975. A poll conducted by the (state-run) centre for sociological research in December 2012 found that 67.5% of Spaniards said they were unhappy with the way their democracy worked. It’s this disdain for the Spanish state in general, rather than merely the effects of the economic crisis, that brought 8 million indignados on to the streets in the spring and summer of 2011, and informed their rallying cry „Democracia Real Ya“ (real democracy now).

But in one village in Andalusia’s wild heart, there lies stability and order. Like Asterix’s village impossibly holding out against the Romans, in this tiny pueblo a great empire has met its match, in a ragtag army of boisterous upstarts yearning for liberty. The bout seems almost laughably unfair – Marinaleda’s population is 2,700, Spain’s is 47 million – and yet the empire has lost, time and time again.

In 1979, at the age of 30, Sánchez Gordillo became the first elected mayor of Marinaleda, a position he has held ever since – re-elected time after time with an overwhelming majority. However, holding official state-sanctioned positions of power was only a distraction from the serious business of la lucha – the struggle. In the intense heat of the summer of 1980, the village launched „a hunger strike against hunger“ which brought them national and even global recognition. Everything they have done since that summer has increased the notoriety of Sánchez Gordillo and his village, and added to their admirers and enemies across Spain.

Sánchez Gordillo’s philosophy, outlined in his 1980 book Andaluces, Levantaos and in countless speeches and interviews since, is one which is unique to him, though grounded firmly in the historic struggles and uprisings of the peasant pueblos of Andalusia, and their remarkably deep-seated tendency towards anarchism. These communities are striking for being against all authority. „I have never belonged to the communist party of the hammer and sickle, but I am a communist or communitarian,“ Sánchez Gordillo said in an interview in 2011, adding that his political beliefs were drawn from those of Jesus Christ, Gandhi, Marx, Lenin and Che.

In August 2012 he achieved a new level of notoriety for a string of actions that began, in 40C heat, with the occupation of military land, the seizure of an aristocrat’s palace, and a three-week march across the south in which he called on his fellow mayors not to repay their debts. Its peak saw Sánchez Gordillo lead a series of expropriations from supermarkets, along with fellow members of the left-communist trade union SOC-SAT. They marched into supermarkets and took bread, rice, olive oil and other basic supplies, and donated them to food banks for Andalusians who could not feed themselves. For this he became a superstar, appearing not only on the cover of Spanish newspapers, but in the world’s media, as „the Robin Hood mayor“, „the Don Quixote of the Spanish crisis“, or „Spain’s William Wallace“, depending on which newspaper you read.

In the darkness of a winter morning, between 6 and 7am, Marinaleda’s workers are clustered around the counter of the orange-painted patisserie Horno el Cedazo. Here they stand, knocking back strong, dark coffee accompanied by orange juice, pastries and pan con tomate: truly one of the world’s best breakfasts, a large hunk of toast served alongside a bottle of olive oil and a decanter of sweet, salty, pink tomato pulp. Pour on one, then the other, then a sprinkling of salt and pepper, and you are ready for a day in the fields. Those with stronger stomachs also knock back a shot of one of the lurid-coloured liqueurs arrayed on a high shelf behind the counter; the syrupy, pungent anís is the most popular of these coffee chasers. All work in the Marinaleda co-operative in shifts, depending on what needs harvesting, and how much of it there is. If there’s enough work for your group, then you will be told in advance, through the loudspeaker on the van that circles the village in the evenings. It’s a strange, quasi-Soviet experience, sitting at home and hearing the van drive past announcing: „Work in the fields tomorrow for group B“. The static-muffled announcements get louder and then quieter as the van winds through the village’s narrow streets, like someone lost in a maze carrying a transistor radio.

When the 1,200-hectare El Humoso farm was finally won in 1991 – awarded to the village by the regional government following a decade of relentless occupations, strikes and appeals – cultivation began. The new Marinaleda co-operative selected crops that would need the greatest amount of human labour, to create as much work as possible. In addition to the ubiquitous olives and the oil-processing factory, they planted peppers of various kinds, artichokes, fava beans, green beans, broccoli: crops that could be processed, canned, and jarred, to justify the creation of a processing factory that provided a secondary industry back in the village, and thus more employment. „Our aim was not to create profit, but jobs,“ Sánchez Gordillo explained to me. This philosophy runs directly counter to the late-capitalist emphasis on „efficiency“ – a word that has been elevated to almost holy status in the neoliberal lexicon, but in reality has become a shameful euphemism for the sacrifice of human dignity at the altar of share prices.

Sánchez Gordillo once suggested to me that the aristocratic family of the House of Alba could invest its vast riches (from shares in banks and power companies to multimillion-euro agricultural subsidies for its vast tracts of land) to create jobs, but had never shown any interest in doing so. „We believe the land should belong to the community that works it, and not in the dead hands of the nobility.“ That’s why the big landowners planted wheat, he explained – wheat could be harvested with a machine, overseen by a few labourers; in Marinaleda, crops like artichokes and tomatoes were chosen precisely because they needed lots of labour. Why, the logic runs, should „efficiency“ be the most important value in society, to the detriment of human life?

The town co-operative does not distribute profits: any surplus is reinvested to create more jobs. Everyone in the co-op earns the same salary, €47 (£40) a day for six and a half hours of work: it may not sound like a lot, but it’s more than double the Spanish minimum wage. Participation in decisions about what crops to farm, and when, is encouraged, and often forms the focus of the village’s general assemblies – in this respect, being a cooperativista means being an important part of the functioning of the pueblo as a whole. Where once the day labourers of Andalusia were politically and socially marginalised by their lack of an economic stake in their pueblo, they are now – at least in Marinaleda – called upon to lead the way. Non-co-operativists are by no means excluded from involvement in the town’s political, social and cultural life – it’s more that if you are a part of the co-operative, you can’t avoid being swept up in local activities outside the confines of the working day.

Private enterprise is permitted in the village – perhaps more importantly, it is still an accepted part of life. As with the seven privately owned bars and cafés in the village (the Sindicato bar is owned by the union), if you wanted to open a pizzeria or a little family business of any kind, no one would stand in your way. But if a hypothetical head of regional development and franchising for, say, Carrefour, or Starbucks, with a vicious sense of humour and a masochistic streak, decided this small village was the perfect spot to expand operations, well – they wouldn’t get very far. „We just wouldn’t allow it,“ Sánchez Gordillo told me bluntly.

Marinaleda’s alternative is decades in the making, but other anti-capitalist alternatives are sprouting in the cracks of the Spanish crisis, in the form of numerous quotidian acts of resistance, not just strikes and protests, but everyday behaviour – the occupation of vacant new-builds by those made homeless by their banks, firemen refusing to evict penniless families, doctors refusing to turn away undocumented immigrants. There is also a new Marinaleda-style farming co-operative in Somonte, a collective farm established on occupied government land in 2012, only an hour or so’s drive from the village. When I visited Somonte earlier this year, I met Marinaleños who had left their home to bring Sanchez Gordillo’s message of „land belongs to those who work it“ to new terrain.

When I visited in February this year, a young man called Román strode bare-chested through the endless fields to greet us, looking strong but tired – they work from dawn until dusk, stopping only to dip into much-needed cauldrons full of pasta, rice and bean stews; surplus vegetables are sold on market day in nearby towns. They were growing beans, pimentos, potatoes and cabbages when I visited, planting trees and trying to resuscitate 400 hectares of idle land – as best they could, with only two dozen pairs of hands. Paradoxically, in light of Spain’s staggering unemployment figures, they still need more people to join their co-operative, and have more farmland than they can currently cultivate. One of the murals painted on the Somonte barn wall contained a telling slogan, alongside portraits of Malcolm X, Geronimo and Zapata: „Andalusians, don’t emigrate, fight! The land is yours: recover it!“ It’s a message cried somewhat into the void, as thousands of young Spaniards scurry down the brain drain to Britain, Germany, France and beyond.

But Somonte is not without support. Hundreds of people have visited at weekends or for short stays, from Madrid, Seville and many from overseas, bringing their labour and other resources, to help with the land, to build infrastructure or paint murals, donating secondhand farming equipment, furniture and kitchenware. As we strolled past a small collection of chickens and goats, Florence, a French woman who had been living in Marinaleda before joining the „new struggle“ in Somonte, explained that the land was some of the most fertile in Spain, but had for decades been used by the government to grow corn, to bring in European subsidies – it created next to no work, and no produce; the corn was left to rot. Those 400 wasted hectares were about to be auctioned off privately by the government when the Andalusian Workers‘ Union turned up in March 2012; they occupied it, were evicted by 200 riot police, and in true Marinaleda style, returned the next day to start again. The auction never took place. Somonte is now 18 months old, growing slowly but steadily, and is the kind of Marinaleda domino effect that the crisis may yet bring more of.

No one ever forgets „that strange and moving experience“ of believing in a revolution, as George Orwell reflected after arriving in Barcelona on the brink of civil war to a society fizzing with energy as it fleetingly experienced living communism. Marinaleda is neither fully communist nor fully a utopia: but take a step outside the pueblo and into contemporary Spain, and you will see a society pummelled, impoverished and atomised, pulled into death and destruction by an economic system and a political class who seem not to care whether the poor live or die. Sánchez Gordillo’s achievements are more than just the concrete gains of land, housing, sustenance and culture, phenomenal though they are: being there is a strange and moving experience, and, as Orwell suggested, an unforgettable one.

In the eight or so years I have known about Marinaleda, I have sometimes had to remind myself of the gap between the grandiose claims made about the village, by left and right alike, and the humble size and intimacy of the place itself. It is a village which means so much to so many people, across the world; but it has only 2,700 inhabitants, and whole hours can pass in which the only noise emanates from a motorcycle speeding down Avenida de la Libertad, or the vocal exercises of a particularly enervated rooster.

It is both poignant and appropriate that Sánchez Gordillo seems to see no bathos, or discrepancy, in devoting as much attention and passion to the local specifics of the pueblo – the need to start planting artichokes this month, not pimentos – as he does to the big picture, persuading the world that only an end to capitalism will restore dignity to the lives of billions.

The indignado movement had informed not just Spain, but the world, that millions of Spaniards were unwilling to brook the crisis. They were desperately looking for an alternative to the current system – and yet, in their midst, there was already one in operation. Faced with the massed ranks protesting in Puerta del Sol in Madrid, in Wall Street in New York, and outside St Paul’s Cathedral in London, the damning questions rang out from conservatives and liberals: „What’s your alternative? What’s your programme? How would it work in practice?“

They may have ignored the village before, or dismissed it with a chuckle as a rural curiosity run by a bearded eccentric; but they can do so no longer. „What’s your alternative?‘ bark the dogs of capitalist realism. Increasingly, the indignados are able to respond: ‚Well, how about Marinaleda?'“

This is an edited extract

Dan Hancox is speaking at Bristol Festival of Ideas on 23 October; details at ideasfestival.co.uk

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/20/marinaleda-spanish-communist-village-utopia

Ein Kommentar